But it's only a theory! or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Uncertainty

No

theory ever agrees with all the facts in its domain, yet it is not always the

theory that is to blame.

—Paul

Feyerabend

When listening to debates between climate activists

(i.e. those who believe in anthropogenic climate change and believe that

something should be done about it) and climate skeptics or deniers (i.e. those

who doubt or deny the existence of climate change), a crucial term often gets

thrown about—a term that is well-known in both the scientific and

non-scientific communities, but that means different things to both

groups. This term assumes center stage

in reasonings and arguments concerning what to do about climate change, what

the proper response should be, and whether climate models are reliable. It hangs in midair like the axe of an

executioner with poor hand-eye coordination, threatening to fall on either side

of the debate, hewing popular response in a particular direction.

This term is uncertainty.

Climate skeptics and contrarians

often appeal to uncertainty when arguing against climate action, by which I mean

adaptive and mitigative measures to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG)

emissions. There’s too much uncertainty to justify taking action, is the

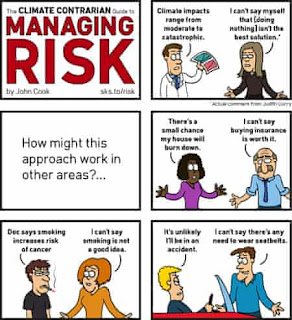

general shape of this argument. As John

Cook shows in the following comic, this argument isn’t sound in the framework

of plausible risk assessment:

Climate

scientists like Stephan Lewandowski argue that contrarians have it backwards,so to speak: “in the case of the

climate system, it is very clear that greater uncertainty will make things even

worse. This means that we can never say that there is too much uncertainty for

us to act. If you appeal to uncertainty to make a policy decision the

legitimate conclusion is to increase the urgency of mitigation.” In terms

of risk assessment, doing nothing is an irrational decision in that the cost of

doing nothing has the potential to drastically outweigh the cost of taking

action.

In

other words, climate activists and skeptics disagree over precisely what the

concept of uncertainty signifies within the scientific debate. No scientific theory is perfect, but that

doesn’t mean the theory as a whole is the source of controversy within the

scientific community: “scientists spend far more time talking about gaps than

non-gaps,” writes Julia Galef, “creating

a skewed impression of how much contention actually exists. People primed to see controversy are liable

to confuse scientists’ disagreement over a theory’s finer points for

disagreement over the theory itself.” Galef

suggests that the tendency toward disagreement between scientists and non-specialists

(or laypersons) is connected to the American values of pluralism and respect

for diverse opinions. Agree to

disagree might be the American way, but it’s not the scientific way; non-scientists

might say they don’t believe in evolution, but for a scientist it’s not a

matter of belief. For scientists, evolution

is all around us, and there’s no viable—meaning scientifically-testable—alternative. The theory of evolution isn’t a personal

belief.

I

recall a moment early in Boston University’s course on climate change (which I had

the good fortune to assist with this semester) when one of the faculty, a

biologist, articulated the discrepancy in how people understand the word theory.

For non-scientists, theories are

selective: you can opt out of them if you wish because they’re only

theories. For scientists, theories are

obligatory: without any other viable framework, you have no choice but to accept

the theory. The only other option is to

enter the realm of fantasy. There is no

such thing as a theory with no gaps in applicability (although some physicists are searching for such a theory, known as a theory of everything), and such gaps aren’t cause for throwing the

baby out with the bathwater. The

reigning theory in contemporary physics—quantum mechanics—remains full of inexplicable

inconsistencies and unknowns. There are

uncertainties, but that doesn’t mean the theory itself isn’t

viable. In fact, uncertainty lies at the

very core of quantum science.

As

Galef says, uncertainty is a feature of science, not a bug. It’s fundamental to the continued inquiries

into a theory, not a reason for its wholesale dismantling in favor of less substantial

beliefs. What’s more, it’s imperative

that we realize—all of us, not just the scientists—that a major source of

uncertainty in science, particularly climate change, is humanity itself:

“The biggest uncertainty in climate forecasting is always us,” Umair Irfan

writes in a piece for Vox assessing the recent federal report on climatechange; “What will humanity actually do

about climate change?” The remarkable

irony of this statement is that the reason humanity is such a source of

uncertainty is that we disagree over what uncertainty signifies. How’s that for a feedback loop? So many see uncertainty in the forecasting

models and think Well, it’s not worth doing anything because there’s so much

uncertainty, without realizing that their attitude is reinforcing the very

uncertainty they’re looking at.

Alternatively, if we were to take action, to reduce GHG emissions and pursue

renewable energy, we would reduce that uncertainty, leading to forecasting models

that actually contain less uncertainty and predict less-extreme variations.

When

James Hansen made his famous 1988 projections, he suffered a slew of criticisms

after subsequent years revealed measurements that didn’t match his models; but his

critics failed to look at the big picture.

Take a look at the original graph, which featured three scenarios:

The actual temperature measurements (the black

line) are much lower than Hansen’s scenario A projection, and mostly lower than

scenario B. Not only that, but look at

how the peaks and valleys don’t match up.

Seems pretty off, doesn’t it? The

problem is that these scenarios aren’t definitive predictions. Each scenario is based on a different set of

assumptions, meaning Hansen is demonstrating potential alternative futures. The most important features of these

projections aren’t their differences from the observed (or measured)

temperature, but their overall trajectory: they all climb alongside one

another. Hansen’s theory may not have

been perfect—it certainly has its uncertainties—but it hasn’t been disproved. To the contrary, it’s been confirmed.

The

different scenarios assume different conditions, including humanity’s

response. When we externalize uncertainty,

perceiving it as an alien and uncontrollable aspect of the natural systems

surrounding us, we cancel our own agency.

We deny the role that we play in uncertainty, and the power we have to alter

it. I’m guilty of this myself. Most of us are. The point I’m trying to make is this: the disagreement

between climate activists and skeptics over the meaning of uncertainty in forecasting

models produces that very uncertainty.

We are the cause of the rationalization for our inaction. I’d call it a self-fulfilling prophecy except

we actually have the power to change it.

If we looked at uncertainty and saw it not as proof of a theory’s flaw

but as a sign of its usefulness and applicability, we could take action to

effectively reduce it. We could realize

our agency within the bounds of uncertainty.

Again, how’s that for

a feedback loop?

Comments

Post a Comment