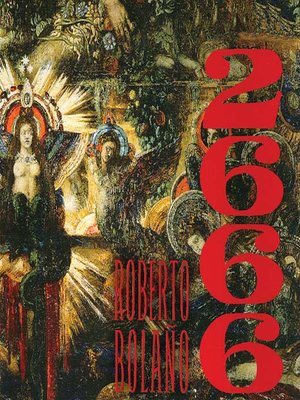

“No one pays attention to these killings, but the secret of the world is hidden in them”: Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 is the Stuff of Nightmares

As I make my way through Roberto Bolaño’s 2666,

I come to a striking realization: this is a book about the ends of worlds.

Not the end of the world, which is far too… Hollywood. But the ends of worlds, the systemic

cancelling of perspectives. Lives burn

out in surreal hallucinations, often delivered in lengthy, detailed dream

sequences: swimming pools that descend to Tartarus, glowing forests, metallic

oceans out of which vague statues grow.

The novel’s first section is a fever dream, structured around the

intellectual and erotic pursuits of four Germanist literary critics. As the section winds on, it becomes clear

that the critics not only seek knowledge pertaining to the identity and

whereabouts of the mysterious contemporary German writer, Benno von

Archimboldi; they seek knowledge about the dread that rises from the fissures

in the earth. They impose meaning on the

miraculous, subject the threshing of life to the vagaries of narrative

interpretation. In short, they intuit

the sacred—or perhaps profane—conspiracy from the workings of the cosmos.

All this makes 2666 sound like a bleak vision of total death, but it’s also a very

funny book. For instance, take the

following ramble delivered by the Mexican professor Amalfitano, whom the

protagonists visit in their search for Archimboldi:

An intellectual can work at the university [of

Santa Teresa], or, better, go to work for an American university, where the

literature departments are just as bad as in Mexico, but that doesn’t mean they

won’t get a late-night call from someone speaking in the name of the state,

someone who offers them a better job, better pay, something the intellectual

thinks he deserves, and intellectuals always

think they deserve better.

Academics

enjoy no immunity in Bolaño’s work, and

2666 is relentless in its often

sarcastic, sometimes incriminating depictions of the modern literary

intelligentsia. These are not heroes to

be emulated but selfish and self-absorbed critics, paranoid interpreters whose

confirmation biases rule their conclusions.

They aren’t the sages we so often imagine established intellectuals to

be, but fools. The metaphor of the ivory

tower looms large in the novel, although largely unspoken; instead its presence

is implicit, manifest in the critics’ interactions with non-academics,

including their violent encounter with a taxi driver.

I haven’t finished the novel yet;

but already halfway through it, I feel compelled to write something about it. Bolaño’s

final work, 2666 was published

posthumously. No one knows why it’s

titled 2666. If you think you hear an apocalyptic ring to

that number, you’re not alone; in a review for the New York Times, Larry Rohter

notes “oblique references in his writing indicating that Bolaño thought of that year as a sort of

apocalypse.” The number never appears in

the novel itself, but that doesn’t change the fact that the text seems pregnant

with revelatory meaning, teasing the thrilling edges of biblical wisdom without

delivering. The novel’s many plots

revolve around the horrific, possibly systematic killings of women in the

fictional Mexican city of Santa Teresa—a feature that Bolaño adapted from the ongoing and unsolved

real-life murders in Ciudad Juárez. It’s

clear that the violent crimes in Central America are central to the

novel as a whole, although their warp and weft aren't yet clear: “No

one pays attention to these killings, but the secret of the world is hidden in

them.” The text doesn’t specify who speaks

these lines; the character who hears them, Oscar Fate, is unable to tell from

whom they come. The uncertainty drives

the surrealism at the heart of the novel, pulling readers into the whispering

insanity—which might be pure, unadulterated rationality—that emanates from the

pages.

Some readers might raise an eyebrow

at the explicit misogyny exhibited by the novel’s predominantly male

characters. I certainly did. 2666’s

men are confused by women, distrustful of them, aggravated by them, and

occasionally violent toward them. If the

backdrop of femicides in Santa Teresa isn’t enough to set your teeth on edge

(although it should be), the presentation of the primary female characters—always

refracted through the eyes of the men around them—ought to be enough to make

you think. I’m always hesitant to

salvage books that I like from the ubiquitous rationalization of reflexivity: It knows it’s being misogynist, It’s

the characters who are misogynist—not

the author, etc. In the case of 2666, I’m comfortable not defending it and

letting others come to their own conclusions; and I’m happy to have that

discussion at another time. For now, all

I’ll say is that the novel’s misogyny, whether intentional or accidental, hews

appropriately close to the depravity that runs throughout the book. By turns funny and horrifying, 2666 is a mysterious vision of something

incomprehensible, and that just happens to be one of my favorite kinds of

narratives.

At the risk of giving away anything

more, I’ll leave you with a brief excerpt—the closing lines of a dream

sequence, experienced by one of the literary critics in the novel’s first

section. As he and his colleagues circle

the absent center that is Benno von Archimboldi, they begin to suffer strange

and disturbing visions, usually at night, such as the following oneiric

manifestation:

And then he spied a tremor in the sea, as if the

water were sweating too, or as if it were about to boil. A barely perceptible simmer that spilled into

ripples, building into waves that came to die on the beach. And then Pelletier felt dizzy and a hum of

bees came from outside. And when the hum

faded, a silence that was even worse fell over the house and everywhere

around. And Pelletier shouted Norton’s

name and called to her, but no one answered his calls, as if the silence had

swallowed up his cries for help. And then

Pelletier began to weep and he watched as what was left of a statue emerged

from the bottom of the metallic sea. A formless

chunk of stone, gigantic, eroded by time and water, though a hand, a wrist,

part of a forearm could still be made out with total clarity. And this statue came out of the sea and rose

above the beach and it was horrific and at the same time very beautiful.

The

ruins of a past civilization?

Premonitions of a climatically changed future? Perhaps both—after all, dreams can have

multiple meanings. Maybe by the end, Bolaño will give us the holiest of holies, open

the seventh seal, as it were… but I doubt it. In 2666,

Bolaño lets his dreams speak for

themselves.

Comments

Post a Comment