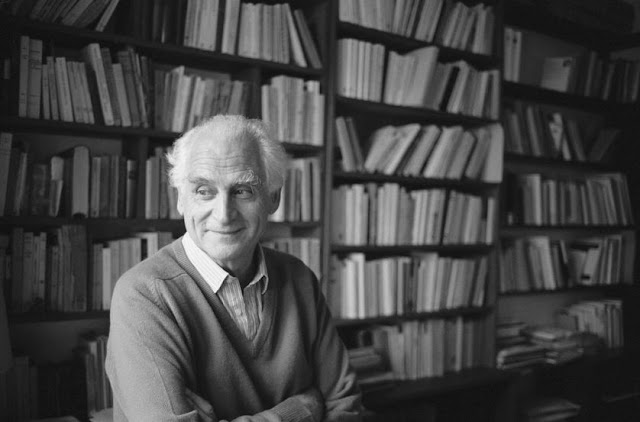

"The book of differences": Michel Serres In Memoriam (9/1/1930-6/1/2019)

The book of differences, noise, and disorder would only be the book of evil for someone who would prohibit the Author of the universe, through calculation, from a world that is uncorruptibly dependable. This, however, is not the case. The difference is part of the thing itself, and perhaps it even produces the thing. Maybe the radical origin of things is really that difference, even though classical rationalism damned it to hell. In the beginning was the noise.

—Michel

Serres, The Parasite

Michel Serres came to prominence during the rise of what

we know today as “science studies”: the humanistic discourses that took science

as an object of sociological analysis.

For science studies, this object is no longer a supreme purveyor of

knowledge, objectively distant and unbiased.

Rather, science studies positions science as a body of knowledge like

any other—political, economic, philosophical, etc.—subject to the prejudice of

experimenters and the limits of instrumentation. Yet Serres’s work is far from the

sociological examinations of his contemporaries, best exemplified in the

rigorous observations of Bruno Latour.

Serres pursued something more akin to a poetic investigation of the

shared intricacies of literature and science—how literature and science cycled

through each other in a series of historical feedback loops—and he was

interested in how the seasons of historical change impacted the way Western

culture perceived its sciences, often unconsciously.

“[…] since Rousseau,” Serres writes, “one no longer

hesitates to invoke science in the realm of law, power, and politics. It is because science has already pointed the

way to a winning strategy.” Serres

was keen on science’s drive to dominate nature, inherent in the Cartesian

rational will; but this dominating drive didn’t define science so much as

characterize the emergence of its modern politico-economic form. Science is never a stable host of ideas or

principles, a set of axioms from which its practitioners venture forth to know

the world. It is a series of evolving

systems, conditioned by the societies in which they appear. “We are in the presence of three types of

systems: the first, logico-mathematical, is independent of time; the second,

mechanical, is linked to reversible time; the third, thermodynamic, is linked

to irreversible time.” The

logico-mathematical system is the one handed down to modern philosophers by the

ancient Greeks; the mechanical is the one devised primarily by Newton and

Leibniz; the thermodynamic one is that devised primarily by Maxwell. Different historical periods, different

conditions of knowledge and perception.

It is only with the third—the thermodynamic system—that we arrive at the

possibility for science studies, for the study of science’s inscriptive

practices (pardon the long quote):

At

the beginning of the twentieth century, communication theory introduced a

series of concepts such as information, noise, and redundancy, for which a link

to thermodynamics was rather quickly demonstrated. It was shown, for example,

that information (emitted, transmitted, or received) was a form of negentropy.

[…] information theory was considered the daughter of thermodynamics;

theorizing immediately began about activities as ordinary as reading, writing,

the transmission and storing of signals, the optimal technique for avoiding obstacles

along their path, and so forth. Of course, the theoreticians of information

theory accomplished this with means inherited directly from the physics of

energies belonging to the macroscopic scale. Success confirmed their

enterprise. Hence, in a parallel manner, the great stability of traditional

philosophical categories but their massive application [now appears] in a different

area: discourse, writing, language, societal and psychic phenomena, all acts

which one can describe as communication acts. […] The system under

consideration becomes a system of signs.

With Serres, we find a

lucid and compelling explanation for why literary humanism (in which I

include not just literary studies, but philosophy, sociology, and history)

finds such power in scientific knowledge.

The signifying practices of science—its means of expression—suddenly

become objects of scientific inquiry: the study of communication and

information.

This isn’t to say that humanists miraculously gained a

foothold on scientific theories of information that scientists didn’t have, or

that they even understood the theories themselves. One doesn’t enjoy an expert’s grasp of Claude

Shannon’s “A Mathematical Theory of Communication” without an expert’s training

in mathematics and thermodynamics.

Serres’s comment doesn’t bestow wisdom on humanists who haven’t done the

work. It does, however, explain the

attraction for humanists interested in scientific practice and history. For Serres, this is no small

convergence. It’s an embodiment of the

engine that drives intellectual pursuit, the feedback between the unthinking

matter of the universe and the thoughtful agent who conceptualizes it—or as

Serres says, “the living organism.”

Serres’s was always a philosophy of humility and

dismantling. He didn’t try to

decontaminate what couldn’t be decontaminated: “This is the paradox of the

parasite,” he writes in his seminal work of the same name; “It is very simple

but has great import. The parasite is

the essence of relation. It is necessary

for the relation and ineluctable by the overturning of the force that tries to

exclude it.” Where scientific order and

knowledge strives for classification, Serres unveils how the very forces it

seeks to classify are always exceeding their limits. As objects of knowledge convey themselves

across differences, they attract different kinds of knowers: “I am passing here

from the human to the exact sciences,” Serres goes on; “my discourse remains

the same—thus noise is the fall into disorder and the beginning of an

order.” There is no absolute beginning

of any entity, no origin to which we can trace any object of knowledge. Serres’s philosophy is more like the logic of

fluid dynamics and nonlinear systems, or what he calls homeorrhesis, a

neologism roughly meaning “same flow”—that is, the same but always changing.

In this respect, and despite his frequent association

with poststructuralism, Serres managed to avoid the former’s rigid categorical

maneuvers, allowing himself a kind of intellectual malleability. Undoubtedly his style of writing has turned

off those inclined to the “exact sciences,” the classifications and tabulations

of scientific practice. Serres never

claimed to be such a scientist, however; he was only ever an acute observer of

the supposed breaks between objects, disciplines, concepts. Squint at them long enough, and you can begin

to make out the continuities that weave them together. “Something exists rather than nothing. The angle is formed; it varies; its space is

fuzzy. It fluctuates.” If we want to be practitioners—experimenters,

engineers, policy-makers—the angles need to be stable and solid. Not so for philosophers, a principle that

Serres abided throughout his life’s work.

He saw opportunity in transdisciplinary connection. He intuited that narrow pathways that give

rise to knowledge by first questioning it.

He developed a methodology of insight.

And yet even in his lyrical and often circuitous style,

we discover a means of carrying out that most elementary of human operations. In an introduction to Serres’s The Parasite,

Cary Wolfe ponders the implications of the philosopher’s writing for the future

of philosophy, particularly as it engages questions of science and

knowledge. “Perhaps it is a question of

what we think ‘thinking’ is,” Wolfe suggests, “not a reflection or representation

but a performance, a practice.” It’s not

uncommon for us to approach writing as timeless, as a system of expression that

circumvents the particularities of its production; but doing so causes us to

forget that these particularities matter—that writing is a form of thinking. As I often explain to my students in rhetoric

and composition, I never know what I want to write until I’ve started

writing it. A counterintuitive

approach no doubt, and one that we necessarily teach students to prune and

shear along the way. I don’t even want

to imagine what it would be like to grade twenty-plus papers by freshmen

versions of Serres, young minds overflowing with questions and opinions. Learning how to write means learning how to

rewrite.

But this doesn’t mean there’s nothing useful in following

a mind at work, attending to the subtleties—often curious, perplexing,

provocative—that propel the creativity of a seasoned intellectual. To the contrary, it can be thrilling. This is the literary component of Serres, the

poetic faculty that informs his philosophy and made his observations so

compelling; for his is a book of differences, noise, and disorder (that is, a

fall into disorder and the beginning of an order).

*All

quotations of Serres are taken from

Hermes:

Literature, Science, Philosophy, eds. Josué V. Harari and David F. Bell,

Johns Hopkins

UP, 1982.

The

Parasite,

trans. Lawrence R. Schehr, U of Minnesota P, 2007.

Comments

Post a Comment